The Death of All Culture.

How to Recover from a Kitchen Apocalypse.

I was supposed to be away from home for two days, but, due to a family crisis (more on that at an appropriate time), one weekend turned into eleven days. When I walked into my kitchen, I gritted my teeth and prepared for the worst. Entire communities had been depending on me for their sustenance, and I’d abandoned them to their fate. There would be hell to pay.

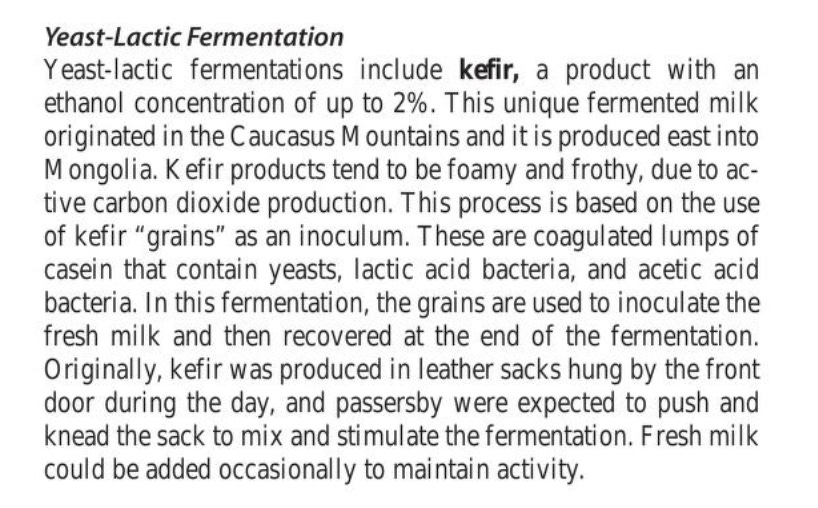

A glance at the container of yogurt in the fridge confirmed my worst fears. My carefully cultured supply of Bulgarian yogurt, maintained with weekly “backslops,” had turned an indescribable, and definitely unappetizing, shade of yellow (distemper, perhaps?). My sourdough starter, which I’d kept alive for five or more years in the back of the fridge with weekly feedings of rye flour, was covered with a greyish surface of slime, and smelled strongly of ammonia.

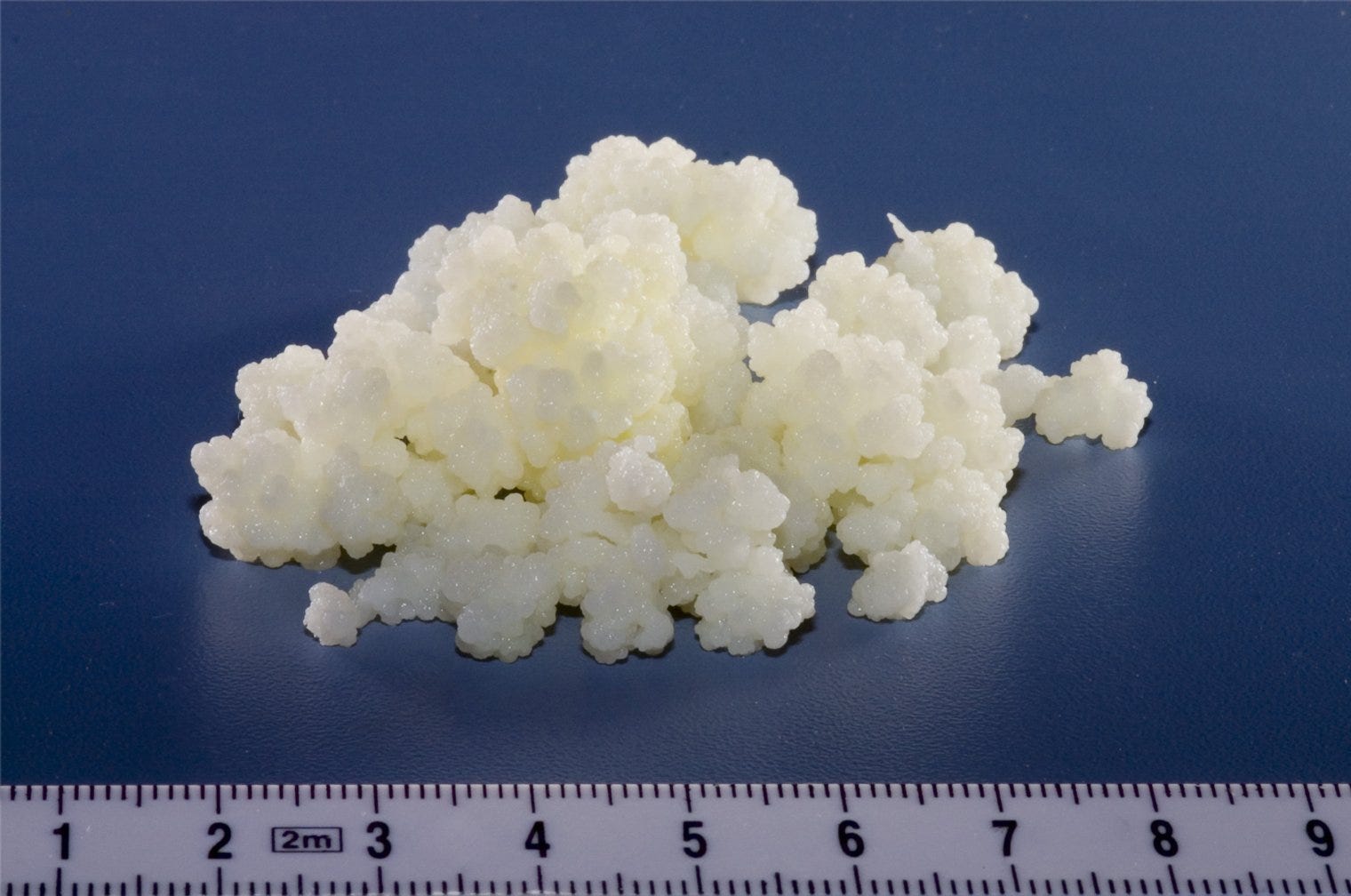

Worst, though, was the state of my kefir. Thinking I’d be gone for less than 48 hours, I’d left a fresh half liter of milk on the counter, in a sealed mason jar, to ferment with a lovingly maintained community of kefir grains. Over 11 days, though, the stable old microscopic order had undergone a complete regime change. It did not smell good, and when I tried to strain the mess, there was no sign of the kefir grains, those slightly rubbery translucent beads responsible for the magic of fermentation: they’d simply dissolved into the acidic kefir and disappeared. What was left?

“Dead kefir grains teem with a kind of life that is something other than kefir,” according to the late evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, “a smelly mush of irrelevant fungi and bacteria thriving and metabolizing, but no longer in integrated fashion, on corpses of what once were live individuals.” Yum.

Down the drain with ye!

The only bright side was the state of my kombucha. I’d bottled a couple of litres before leaving, and the “mother” was snoozing, safe in suspended animation, in a sealed jar in the door of the fridge.

I’d come home very sick in body. You can call me a hippie, but I attribute this to a breakdown in my gut microbiota, brought on by airplane and airport “food,” the insipid melted cheese product they cover everything with in Vegas, and being separated from the healthy microorganisms (kefir, kombucha, kimchi, yogurt, sourdough) that populate my gut when I’m at home. Normally my body deflects all pathogens, like a fully caffeinated Ninja. With my microbial shield compromised, a stray virus was apparently enough to take me down. (And this sickness, whatever it was, definitely started with an ominous rumble in the belly.)

I have now set about restoring the Old Kitchen Order. Sourdough turns out to be very forgiving. After scraping off the grey slime, I found enough healthy-looking goo to feed with rye flour (115 grams starter, 115 grams lukewarm water, 115 grams rye flour, let rise in Tupperware for half a day, then back into the fridge). I remember a “Sourdough Hotel” at the Stockholm Airport, where home bakers with separation anxiety could leave their precious babies in a fridge, with a guarantee of weekly feedings. Not sure if it survived the pandemic…

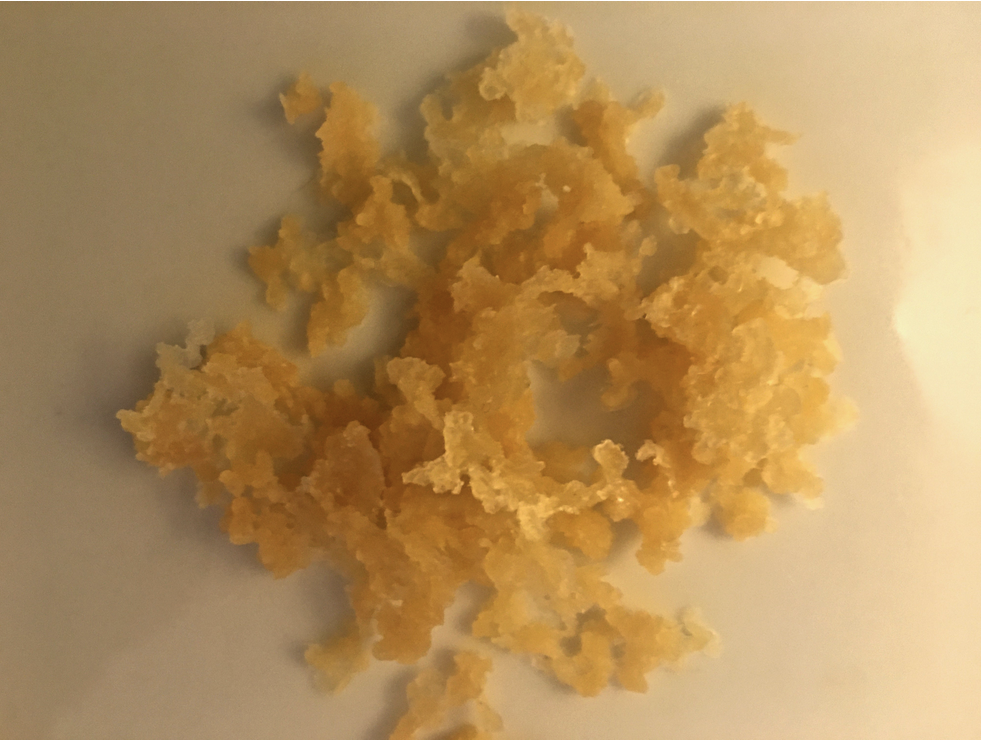

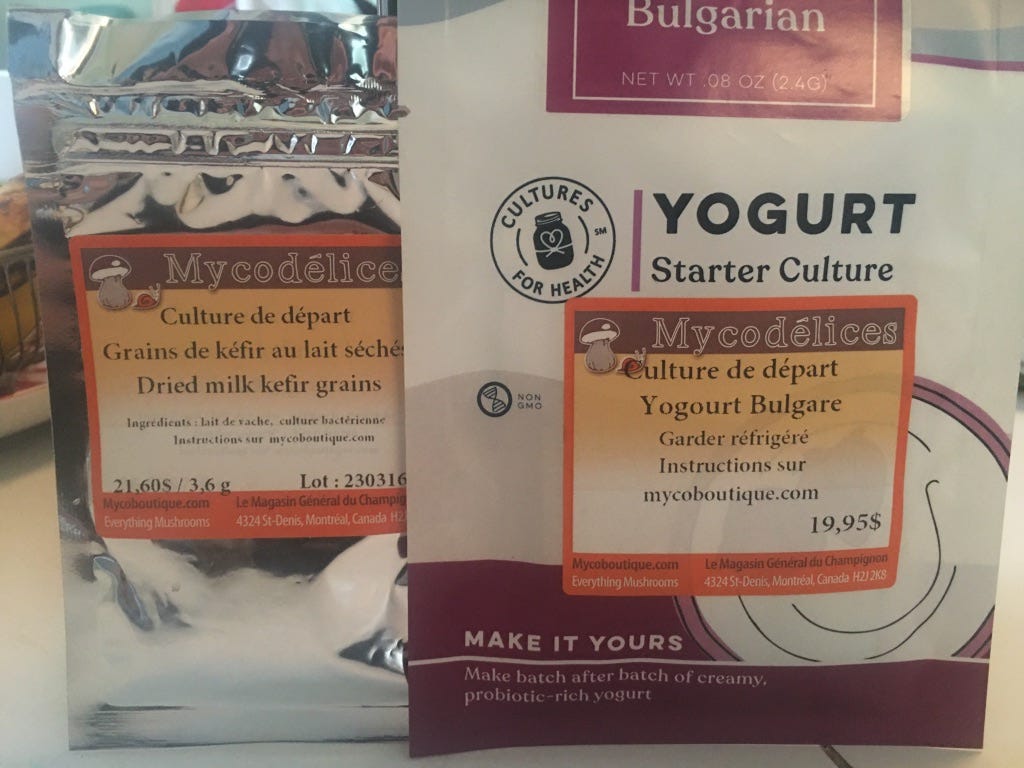

I rode my bicycle down to Mycoboutique, Montreal’s HQ for all things ’shroom related, and bought refrigerated foil-packs of Bulgarian yogurt culture and dried kefir grains. Not exactly cheap, but a great investment. Once you get the process rolling, the cost of your kefir and yogurt (whose retail price now hits $6.99 for 750 ml where I live) becomes the price of the feedstock—in other words, whatever you’re paying per litre or gallon of milk.

I got the yogurt going, slowly heating a quart of milk to 160 degrees F, then letting it cool to 110 F, and slopping it with the culture into the yogurt-maker I’d picked up to ferment sardines into garum. (See my earlier fish-sauce posts.)

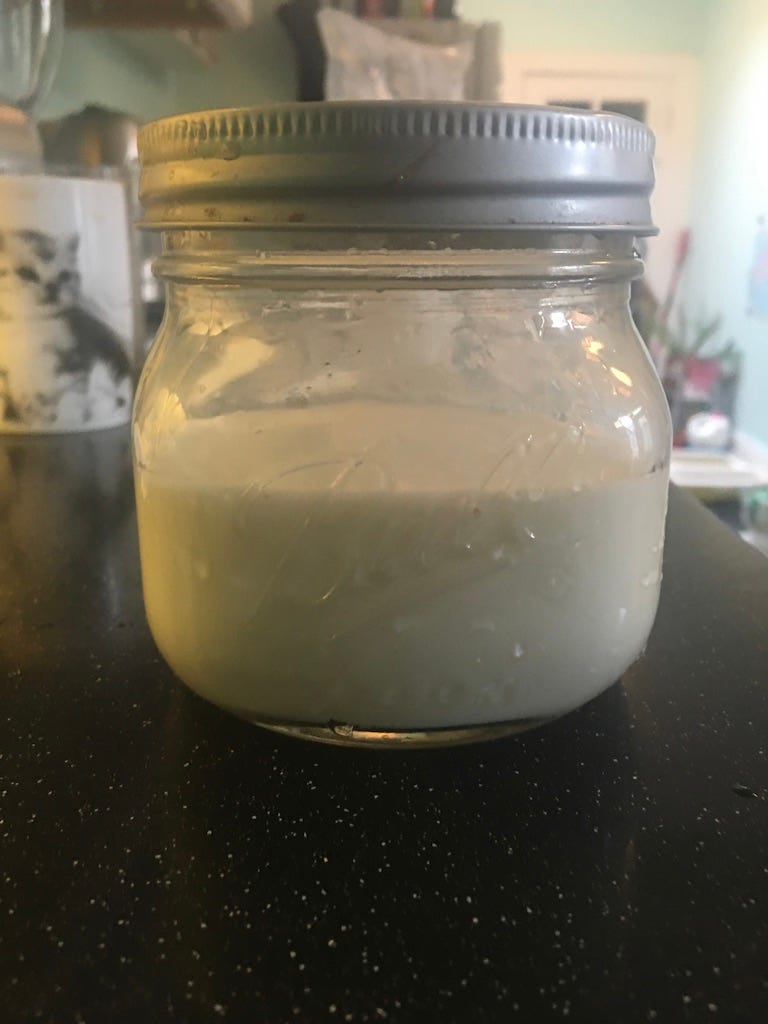

But my real priority was the kefir. The yellowish, dried grains (see above) smelled a bit cheesy, not unpleasant at all. I added them to one cup of whole (3.25% MF) milk in a sealed jar, which I’m leaving on the counter near a lamp, to make sure it falls into the 68 - 86 F (20-30 C) range you need for fermentation to occur. By around dinnertime today, I’ll chuck the first batch of milk, then add the rehydrated grains to 4 cups of milk, and let them ferment for another 24 hours. Then I’ll strain them through a colander, put the transformed milk into a sealed jar, where it will start to fizz (and yes, some ethanol may be produced; I’ll just have to take that bullet). Then into the fridge; the strained grains are added to another litre of milk. Repeat, ad infinitum, but never ad nauseum. The first batch takes some doing; after that, it’s five minutes’ work, max., every day or two. At this point, my gut can’t wait for midweek, by which time I should be back on the kefir train, drinking that thick, tart, fizzy nectar of the nomads again.

When all is going well, I drink about a cup of chilled kefir a day. In terms of macro- and micronutrients, its benefits are pretty similar to those of milk. (It’s up to 30% lower in lactose, though, so many intolerant types can digest it more easily than liquid milk.) The real benefit comes from all the germs swimming around in the soup. Kefir grains are an example of a SCOBY, a symbiotic community of bacteria and yeast. Some of these 30 microorganisms are familiar, such as Lactobacilli (our sourdough friends), and Saccharomyces (brewer’s yeast); but apparently half of them have yet to be isolated.

Kefir’s origins lie in the North Caucuses, with its legendary center of origin lying around Mount Elbrus, a dormant volcano in southern Russia. According to this microbiology textbook, kefir was traditionally made in goatskin sacks hung by the door, meant to be jostled by those entering to ensure the mixing of the grains.

Here’s the weird thing about kefir, and why my letting my grains die felt like such a failure to me. According to Margulis, kefir grains do not possess “programmed death”; they can theoretically live forever. Just as the foundations of multicellular life lie in that time, 1.45 billion years ago, a primitive cell swallowed a bacterium—these enslaved bacteria live on as the mitochondria that power human cells—the SCOBY in kefir is, in the words of fermenting guru Sandor Katz, “a spontaneous symbiosis—or a number of them—that has perpetuated itself.” Feeding this community with the milk of ungulates allows that relationship to continue, potentially for eternity.

In a fascinating essay* in Scientific American, Margulis wrote that “the prophet Muhammad gave the original kefir curds to the Orthodox Christian peoples near Mount Elbrus with strict orders never to give them away. Nevertheless, secrets of preparation of ‘Muhammad pellets’ have been shared.” She also makes a strong case that the kefir grains in my kitchen are potentially immortal. “Although the kefir curd is a complex individual, a product of interacting aggregates of bacteria and fungi, it does not reproduce by sex. Rather the kefir curd, which has no sex life, enlarges by direct growth, division and death of its components. When mistreated by adverse environments, it disintegrates and dies. And, like any live individual, it never returns to life as that same individual.”

By neglecting my grains, I created an environment beyond adverse, cheating them of potential immortality. I’ll do better next time, guys, I swear.

Which reminds me, I better go give that jar a good shake.

- “Sex, Death, and Kefir”: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/sex-death-kefir-lynn-margulis/