Tasting Silphion

Because the Proof of the Pudding Is in the Eating

Because the Proof of the Pudding Is in the Eating

In my last Lost Supper dispatch, I told the story of how I took a high-speed train to central Turkey with Mahmut Miski, a professor at the University of Istanbul, who made the case that he’d discovered the mystery herb of the ancient world growing on the flanks of an extinct volcano near the city of Askaray. Here’s the rest of the story.

After our expedition to the orchard near Mount Hasan, Professor Miski and I took a train back to Istanbul. After taking a stroll around the bazaars—Spice, Fish, Flower, and Grand, always an intoxicating experience—I met Miski outside the gates of the University of Istanbul, and we walked to the Faculty of Pharmacy, which was housed in the former residence of a nineteenth-century Ottoman pasha. In the lobby, we were greeted by Galen, Hippocrates, and the Persian physician Avicenna, whose busts gazed benevolently over potted fig trees…

Miski explained that he had been trained in pharmacognosy, the study of plants as the source of useful medicines. The once-flourishing field has lately fallen out of fashion. Pharmaceutical companies have run into intellectual property challenges from indigenous peoples, who rightfully question the way the developed world turns traditional plant remedies into patented medicines for profit.

“Big Pharma has no patience,” lamented Miski. “They want everything the next day. Synthesizing a plant compound block by block is very time-consuming, very expensive. If it is difficult to make something in huge quantities, they simply drop it.”

We made a stop in the faculty’s herbarium, where dried plant samples were preserved in dusty folders in rows of tall filing cabinets, and then walked up a broad marble staircase to the faculty’s labs. Over demi-tasses of sludgy-sweet Turkish coffee, Miski introduced me to the graduate students who had assisted him in isolating the plant’s secondary metabolites. Their lab, the students explained, had good equipment for carrying out liquid and gas chromatography analyses, but what they really needed to finish the job was a nuclear magnetic resonance machine. There was only one in Turkey, and getting permission to use it was difficult. Miski hoped that one of his grad students would get a fellowship to study in the United States, where accessing such machines is easier.

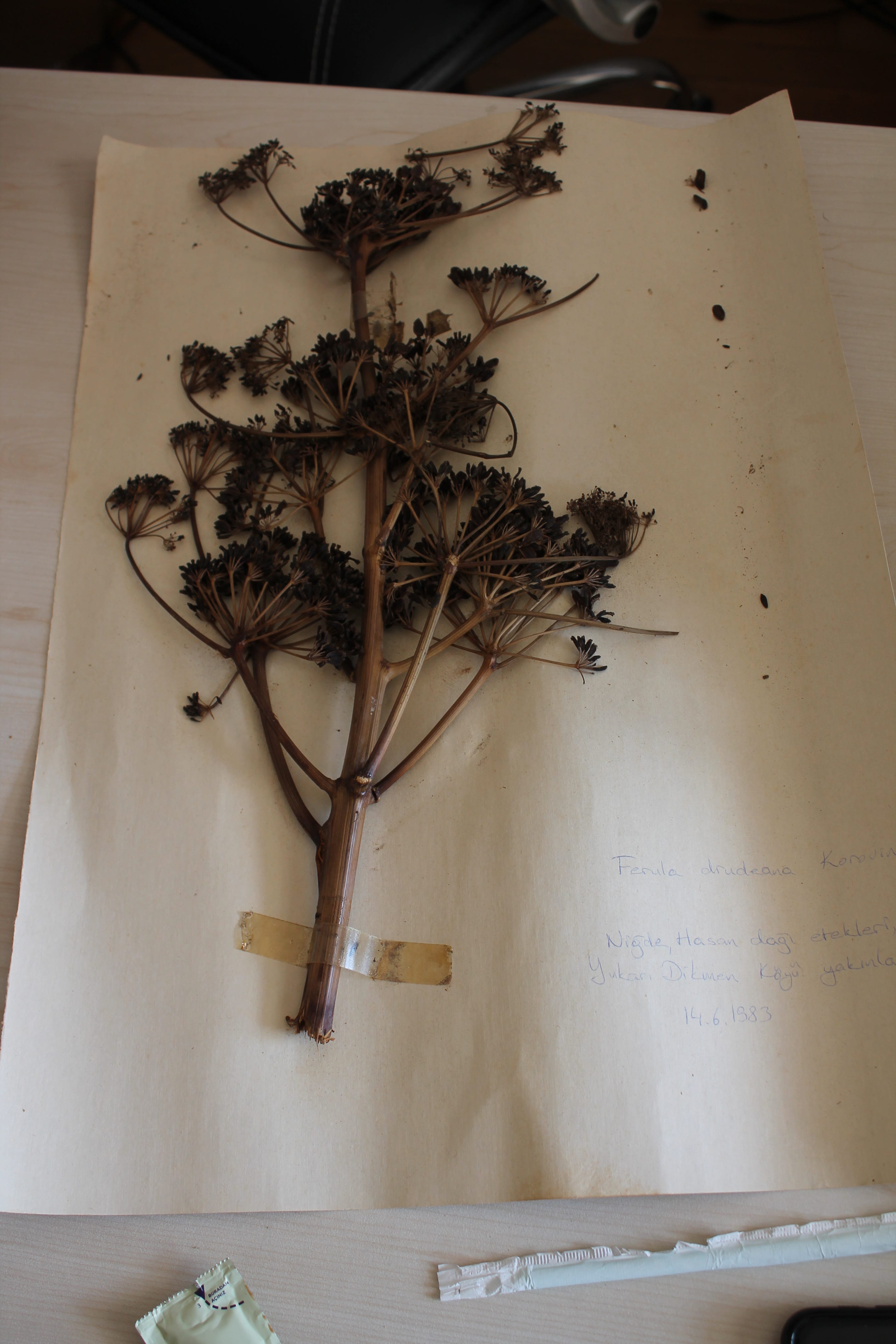

One of his students brought a beaker from a fridge, which contained an amber-colored liquid, extracted from the sliced and ground root. Miski explained that it contained all of the potentially interesting medical compounds from the Drudeana resin; many of them had cancer-fighting, contraceptive, and anti-inflammatory properties. It was especially high in shyobunone, which acts on the brain’s GABAa receptors, and may contribute to the plant’s intoxicating smell. Opening the folder from the herbarium, he showed me the samples he’d collected almost forty years earlier. They were attached with brittle tape to a yellowing page, on which the date “14.6.1983” was written in ballpoint pen. The papery fruits resembled the lobes a Valentine’s heart, and the grooved stalk and dried-out flower clusters looked a lot like the images on the ancient coins.

On my last full day in Istanbul, I met Miski at the Nezahat Gökyiğit Botanical Garden, which occupies an unlikely setting among the glass towers of Istanbul’s financial district. Miski explained that a Turkish businessman had established the gardens after his wife died of lung disease. In an effort to reduce air pollution, he’d built the gardens in four loops of an enormous freeway cloverleaf on the Asian side of the city, with the sections connected by tunnels beneath the roads. We rode an electric cart to the Anatolian section, which was shaped like the map of Turkey. Near a mound meant to represent Mount Hasan, Miski showed me plots of soil, where Ferula drudeana plants had been planted by the staff. Miski inspected the ground, but the basal leaves that announced the appearance of the stalk wouldn’t appear until spring.

At a picnic table next to the gardens’ greenhouses, Miski told me he wasn’t concerned about the plants; they would flower in good time.

The number of plants in the wild is so low, in fact, that Ferula drudeana officially qualifies as a critically endangered species. Miski confessed that he was still agnostic on the issue of whether the plant was the original silphion; he was happy to have identified a species with so many potentially useful disease-fighting compounds.

=====

The following spring, Miski returned to Dikmen, where his old friend, orchard owner, Mehmet Ata had been monitoring the plant’s development. Snowmelt from Mount Hasan had abundantly irrigated the site, and the field was a riot of brilliant yellow flowers. At least sixty of the plants were in full bloom, which meant the roots would have been at their most pharmacologically active. As Miski approached the site, he had to chase away several goats, who, attracted by the intoxicating odor, were trying to make a supper of the leaves.

I decided to fly to Istanbul a second time. To satisfy her curiosity about the plant, Sally Grainger had agreed to travel to Turkey from her home in England. You may be familiar with Grainger from previous Lost Supper dispatches; I consider her the “Julia Child of Ancient Cooking.” A former pastry chef with a degree in classical archaeology from Royal Holloway, she is the author of the definitive book on the ancient Roman fish sauce, The Story of Garum. Grainger also demonstrates ancient Roman cooking techniques on this YouTube channel, which is filmed in her backyard in East Hampshire.

We met at the Nezahat Gökyiğit Botanical Garden, which occupies an unlikely setting among the glass towers of Istanbul’s financial district. (Miski explained to us that a Turkish businessman had established the gardens after his wife died of lung disease. In an effort to reduce air pollution, he’d built the gardens in four loops of an enormous freeway cloverleaf on the Asian side of the city, with the sections connected by tunnels beneath the roads.)

Next to an enclosure where the garden’s peacocks strutted, Grainger helped employees set up a makeshift outdoor kitchen. She had packed a mortar and pestle, and all the spices and condiments needed to recreate recipes from Apicius—the definitive collection of Roman recipes, compiled between the 1st and 5th centuries—including sweet wines, the fermented fish-sauce garum, and herbs such as rue and lovage. As she ground cumin and pepper, and terracotta pots full of lentils stewed over charcoal braziers, Miski showed her a thick, ridged stalk of Ferula drudeana, with pearl-colored sap oozing from a fresh cut. She began by dropping a bit of hardened resin into a pan of heated olive oil, the first step in making laseratum, a simple silphion-based dressing.

“I’m getting a very great sense of culinary value,” said Grainger, as the fumes perfumed the air. “It’s intense and delightful. Earthy, I’d say, and mushroom ‘green.’ When you smell it, your saliva flows.”

Enlisting Miski and myself as sous-chefs, Grainger set to work on half a dozen recipes, being sure to make versions flavored with asafoetida (a related Ferula species, used as a seasoning in India, where it is known as hing; you can read more in this dispatch on the “Devil’s Dung”) for contrast.

As picnic tables began to fill with plates of finished Roman dishes, a crowd, which included the botanical garden’s directors and staff and Miski’s students, gathered around for samples. A bowl of aliter lenticulum, lentils made with honey, vinegar, coriander, leek, and Ferula drudeana, was deemed complex and delicious, while the same dish made with pungent asafoetida resin provoked grimaces, and was left largely untouched. Squash sautéed with the plant’s grated root was also eaten with gusto, as was a delicate dish referred to in Apicius as isicia, in which prawns are pounded with lovage and cumin and boiled, with the resulting dumplings dipped in the laseratum sauce. The biggest success, though, was ius in ouifero fervens, a sauce for lamb made with sweet wine and plums spiced with an ample dose Ferula drudeana.

“It’s beautiful!” said Grainger, as she rested in a lawn chair after a long day on her feet. “Even though the sauce is rich and dense, the flavor of the silphion isn’t buried by the fruits and spices. It has this intense ‘green’ flavor that actually brings out the qualities of the other herbs in the sauce.” A version made with asafoetida was obnoxiously pungent. It seemed Grainger believed Ferula drudeana had great gastronomic merit, and was a good candidate for being the long-lost plant of the Greeks and Romans.

“Oh yes,” she replied. “I’m tasting silphion in a botanical garden in Istanbul! It’s a fascinating plant, and I can understand why the Romans craved it. Quite apart from its medicinal qualities, whether it was a soporific or a stimulant, it just tasted great!” She was already thinking of how to us pine nuts or flour, the way the Romans did, as a technique for making a little of the precious resin go a long way.

Miski seemed pleased with the results of Grainger’s experiments, and surprised by the flavor, though he confessed he was concerned about what might happen next.

“There are only six hundred individual plants we know of in the whole world,” he pointed out. Three hundred of them grow in the wild. An equal number are now being grown from seed in the botanical gardens, though it will take several years before any of them are mature enough to produce fruiting bodies. “You’d have to grow a thousand times as many plants to produce a commercial supply.” For the time being, numbers are so low that Ferula drudeana officially qualifies as a critically endangered species.

“That’s what’s stressing me out,” said Miski, a genuine note of alarm in his voice. “If everyone starts making silphion sauce, wait! We’re not going to have enough to go around.”

Two thousand years after the original supply of silphion was cut off, the legendary plant may have reemerged only to face a threat from its ancient nemesis: human appetite.

For all the details (including references to books and articles cited), see the “Lost and Found” chapter of my book, The Lost Supper: Searching for the Future of Food in the Flavors of the Past, which has just been published by Greystone.