Kitchen Time Travel

Going back 12,000 years while I wait for the ricotta to cool.

Between research trips for The Lost Supper, I’ve been playing around with fermenting dairy products at home. I started with kefir and yogurt, which are pretty easy, but require an investment. In the case of kefir, you have to obtain kefir crystals, the symbiotic community of bacteria and yeast responsible for souring the milk ($19 in Montreal); with yogurt, you need culture—I opted for Bulgarian, $24 for two packs—and a yogurt-maker ($70). (You can make yogurt in the oven, but it requires more supervision.) Once you’re set up, though, you can go on making kefir and yogurt pretty much forever—unless, that is, some unforseen circumstances remove you from your kitchen for an extended period. (A catastrophe I describe in The Death of All Culture.)

My first rudimentary attempt at cheese-making turned out to be a lot less costly—I already had everything I needed on hand in my kitchen. (The only really specialized equipment was a thermometer.) I started with four cups of full-fat milk, which I poured into a thick-bottomed saucepan, and began to heat, very slowly, stirring with a wooden spoon at least once a minute.

I’ve been reading the fascinating new book Spoiled: The Myth of Milk as Superfood, by Anne Mendelson, which makes the case that consuming “drinking-milk,” as she calls fluid or liquid milk, is a recent phenomenon. Only 35 percent of humans can digest the lactose in liquid milk beyond the age of seven or eight; most of those who can are of European descent (hence the repulsive spectacle of shirtless Proud Boys chugging milk to prove their racial “purity.”) The European settlers of North America were able to promote a glass of milk as a superfood thanks to pasteurization and refrigerated supply chains. (Remember that “Got Milk?” campaign from the 90s?) For two-thirds of humanity, consuming liquid milk is a surefire prescription for farts, diarrhea, and a burbly tummy.

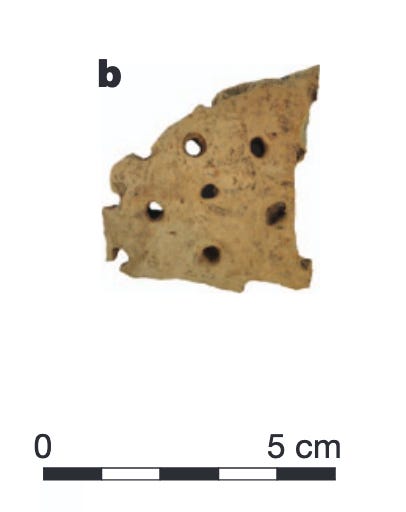

Fermented milk, on the other hand, is widely consumed throughout the world. Humans were probably eating cheese before we drank liquid milk (from anyone other than our mothers, that is). The earliest evidence of cheese-making yet discovered is the shard of clay pottery with tiny holes for straining curds pictured below. It was discovered in Kuyavia (Poland) in the 1970s, and subjected to the lipid analysis that confirmed the presence of milk proteins in 2011. It dates from 7,400 years ago.

Whoops—I almost forgot the milk I’m heating on the stove. I’m slowly bringing it up to 190 degrees F (about 88 C), which takes about half an hour. Got to keep stirring it, so a skin doesn’t form. (Though I’ve lately come to enjoy the texture of milk skin, plucked straight from the pot, which really disgusts my kids.)

Of course, we were probably eating cheese well before 7,400 years ago—the current thinking is that widespread cheese-eating goes back to at least 12,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent. Because fermentation turns the nutritious sugars in liquid milk into digestible lactic acid, cheese contains only residual levels of lactose. This means that everybody—except the most severely lactose intolerant—can digest such fermented dairy products as butter, kefir, yogurt, and cheese. (This explains why China, where lactase persistence is rare, has nonetheless become the world’s largest growth market for cheese.) Liquid milk will coagulate into solid curds when you add rennet—the complex of enzymes found in the stomachs of young ruminants that allows them to digest their mothers’ milk—or such acids as lemon juice and vinegar. The first cheese humans ate may have come in the form of the solids they found when they cut open the stomach of an auroch or a goat.

As the milk heats, I add a quarter cup of lemon juice (pulp sieved out). By the time it’s reached 190 F, the milk is already separating into curds (solids) and whey (liquid). Then I take the pot off the stove and let it cool for about 10 minutes.

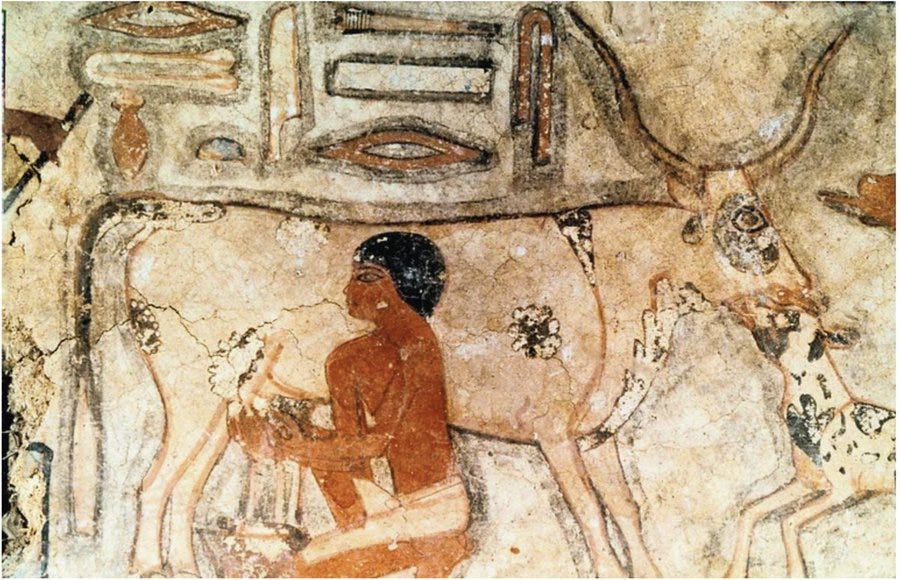

The world's oldest intact cheese, by the way, was found in the 3,200-year-old tomb of Ptahmes, mayor of Memphis in Egypt. Fun fact: it was contaminated with the bacteria that causes brucellosis, which means that consuming it would have led to a fatal case of food poisoning (just desserts for grave robbers?)

After the curdled milk has cooled, I pour it into a colander lined with cheesecloth, and let the whey drain through into a bowl. Then I gently squeeze the drained curds, and stir in 2 tsps (or just under) coarse salt. (I’m doing with a colander what Neolithic herders were doing with those clay strainers discovered in Poland.) Finally, I chill it in the fridge (a luxury, admittedely, not available 7,400 years ago, though there might have been mountain streams to plunge a clay pot into for quick cooling).

And, twenty minutes later, Ecco: ricotta! Really fresh ricotta, better than anything I can buy in as store. It’s silky and creamy, great on its own, and amazing combined with bucatini and tomato sauce for a summery-y, nourishing pasta dish.

Seem like a lot of work? Maybe. But I’m not just making cheese, I’m time travelling. I like to remember that our Neolithic/Paleolithic ancestors—who were anatomically- and behaviorally-modern humans—had exactly the same cognitive capacities as us. They were smart, resourceful individuals, and they devoted a lot of their intelligence to solving the consuming problems of shelter and food. Every time I do a food experiment like this one, I feel like I understand something more about what it is to be human.

I’ll leave you with a quote, from the historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto’s Near a Thousand Tables:

“The history of hunting and herding is reenacted in cheese. In a phase corresponding to the hunt, exposed milk is left as a trap for bacteria gathered at random. The discovery follows that certain beneficial effects can be guaranteed by regulating the conditions under which milk is left to sour: in effect, this means that particular bacteria are being ‘herded.’1 Nowadays, mass production delivers a substance which hardly seems worthy of the name of cheese: pasteurization destroys the relevant bacteria at the start of the process and the desired effects are engineered instead by the introduction of selected cultures.”

If you’re enjoying these dispatches, I’ll hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription. This Substack writing is an experiment—so far, I’m enjoying it, but I’m going to need some encouragement from readers to keep it going, and to keep the family in milk money.

One quibble: the bacteria aren't really "gathered" from the environment, as is sometimes the case with sourdough bread. With cheese, they're present in the raw milk already. ↩