How to Make Neolithic Flatbread

Recreating the World's Oldest Daily Bread—Pt. 1

Recreating the World's Oldest Daily Bread—Pt. 1

During the writing of The Lost Supper, I had a goal that became an obsession: recreating the bread that was consumed at Çatalhöyük, a proto-city whose ruins I visited in central Turkey. It was the first place where humans lived together in large numbers. Eight and a half thousand years ago, Çatalhöyük (pronounced cha-TAHL-hu-yook) was home to as many as eight thousand people, making it the single largest concentration of humans that had ever lived on earth.

Fresh-baked bread provided the long-lived people of Çatalhöyük with a large percentage of the calories in their diet. It was made with a kind of wheat the ancient Babylonians called ziz, the Egyptians called zeia, the Hebrews referred to as kassemet, and contemporary Turks know as kavilca. In English we call it emmer. Along with barley, it was the first wild grass ever domesticated, putting it among the most ancient of the ancient grains.

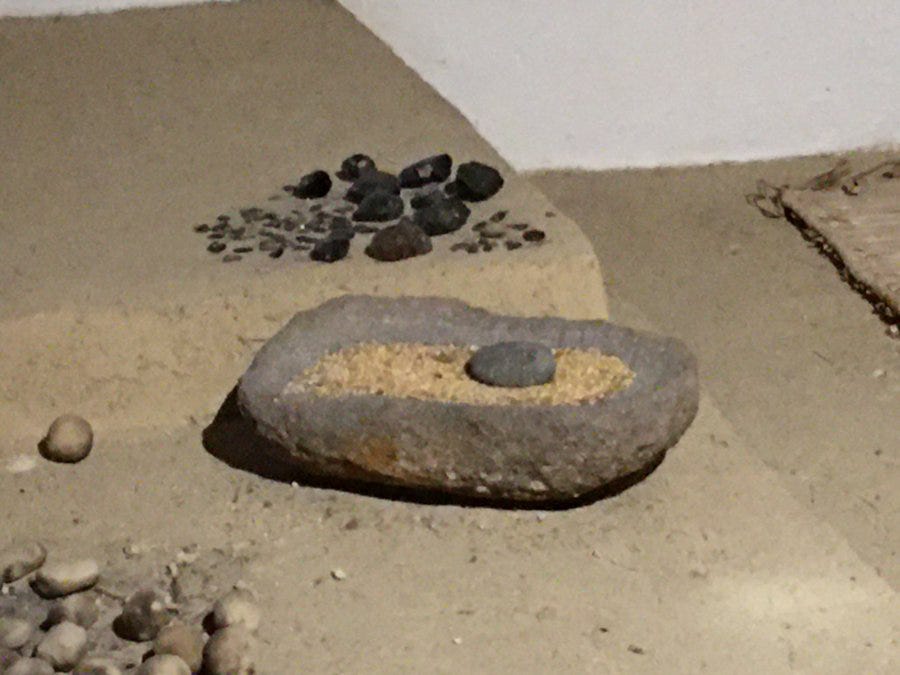

On the Çatalhöyük site, I found replicas of the saddle querns that people there used to grind the emmer into flour, as well as the ovens used to bake the dough into bread. They resemble firins, the beehive-shaped ovens used in villages in contemporary Turkish village to make ekmek (bread, but also the Turkish word for food or sustenance).

I wanted to know what Neolithic flatbread tasted like. My challenge, once back in my hometown of Montreal, was to bake my own, staying as close to the original techniques as possible. Here is the replica oven I saw on the Çatalhöyük site; to the right is a hearth, where coals and embers could be raked.

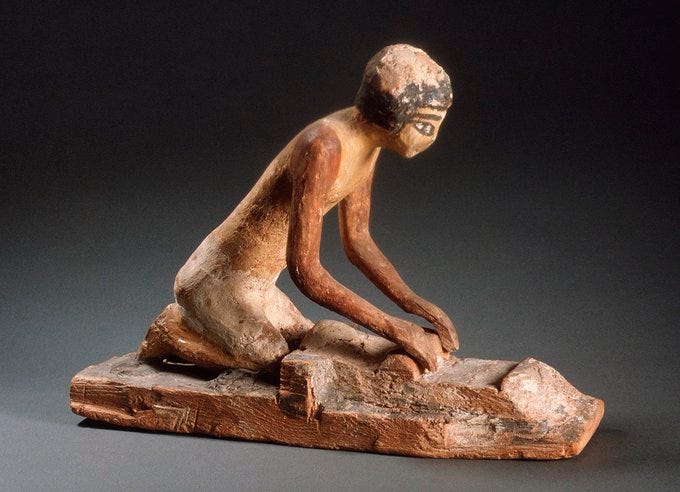

And here is the quern, with the oval-shaped grindstone. It was likely made of andesite, which was abundant in the area.

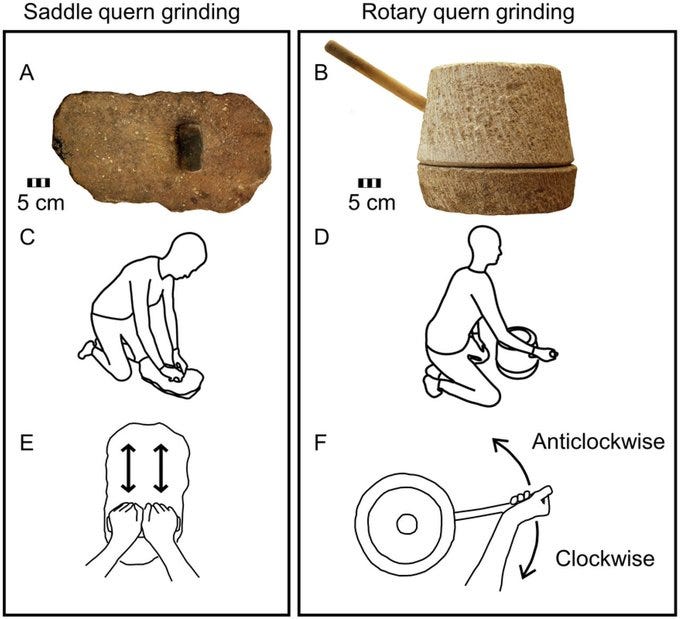

Lara Gonzalez Carretero, a British Museum archaeobotanist who has studied the bread culture of Çatalhöyük, told me that the closest thing to a Neolithic saddle quern in North America would be a metate, which is used in Mexico to grind corn into masa flour for tortillas. The model I’d chosen had a nine-by-twelve-inch surface, supported by three pudgy legs, and weighed thirty pounds, which made me confident it would be sturdy enough to get the job done. I ordered it from an online shop in Oaxaca, and it arrived more or less intact.

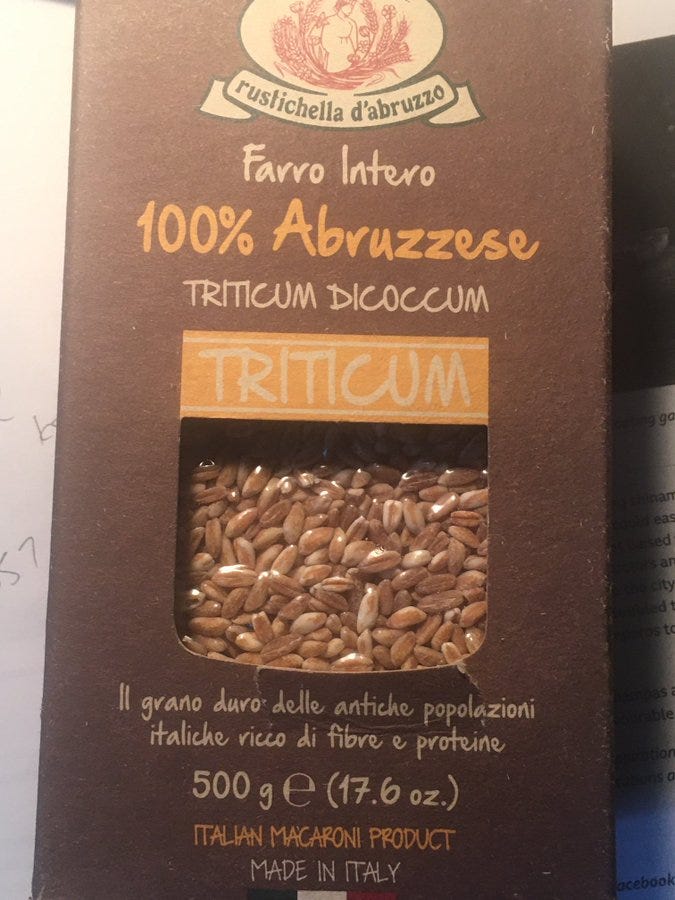

The next step was to find the ancient grain used by Çatalhöyükans. They probably first gathered emmer in the wild, but then began to grow it near the settlement. The Latin name Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccum. Italians call it farro—which I found at a grocery store in Montreal’s Little Italy.

In spite of the scientific name on the package, I wasn't completely confident about this Italian grain (sometimes it's another “ancient” grain, spelt), so I ordered some from an organic supplier in western Canada. Emmer is a beautiful grain! Very hard, silky and glistening between the fingers. Each grain is about the size of a mouse turd, if you’ll excuse a non-beautiful analogy.

I’d been making sourdough for the last eight years, but I’d never ground my own grain. So I took my emmer and my metate to legendary Montreal baker Marc-André Cye, formerly of Olive & Gourmando, and now better known “Baker on the Go” (His handle on Instagram). Here we are at his HQ on The Main.

Marc-André was really intrigued by the project. He’s ground grain mechanically before, but never on a quern. Here are the first passes with the grindstone (or mano) on the metate. It is clearly designed to roll over corn (maize) rather than wheat. The pores in the basalt were huge, but they quickly filled with flour, providing a smoother surface. Marc found tiny flecks of stone in the first batches of flour, so we threw those out. (Ancient Egyptian teeth were worn down by microabrasions, probably for this reason.)

Marc had taught me the technique, so at home I got to work grinding enough emmer to make the flatbread. I found 4 tsps, about 20 grams, was a good amount to do per batch. Each batch could take up to 7 minutes to grind into flour. The technique is pretty intuitive—back and forth grinding. (Almost like the quern was a set of molars, part of the pre-digestion process.) But it's physically demanding. It worked better when I put it on the floor, kneeled, and put my full weight into the mano-grindstone.

I averaged about 120 grams per hour. My back was sore for days; the spasms in my upper arms lasted for days; I got blisters on my palms! Making bread was time-consuming and exhausting—people must have really wanted it. At one point I recruited my youngest son (here he is, dressed as a Pokémon trainer). He only lasted a few passes; you really need to get your back into it.

It took me four hours, in two sessions, to grind enough for a “daily bread” make. The flour smelled great, by the way, woody, complex, nutty.

(Grinding grain seems to have been a gendered activity in Egypt; wear-and-tear on skeletons suggests the task fell disproportionately on women. Not in egalitarian Çatalhöyük, where the houses were all of roughly the same size, and the archaeological evidence suggests men and women shared in grinding tasks.)

Once I had enough flour, I was ready to set about making the dough. I’ll walk you through the rest of the process in next week’s dispatch…