Eating the Alps

I Visit the Headquarters of Mountain Food in a Monastery in Switzerland

// Last month I spent a whirlwind week in Switzerland, riding public transport using the amazing, all-inclusive Swiss Travel Pass from SBB, the national rail operator. (Remember that movie Planes, Trains and Automobiles, where every form of transport fails for Chicago-bound Steve Martin? Imagine the Swiss version: Trains, Trams, and Funiculars, where everything actually worked, and the hero gets to every appointment in comfort, and on time.) I was lucky to have time for a stop at the Culinarium Alpinum, in the village of Stans, near Luzern.

I love sampling local foods, and I love hiking in the mountains. I've come to believe that mountain food is in its own category. I've had llama steak and coca tea in the Andes, cloud-like momos and pots of yak butter tea in the Himalayas, and baked beans and bison in the Canadian Rockies. But Europe offers the most intriguing and complex cuisine I've ever encountered in mountain settings. That's why, when I learned there was an institution devoted to culinary heritage of the Alps—specifically the gastronomy of the Swiss Alps—I knew I had to pay a visit.

I took a train ride from lakeside Luzern, in the center of Switzerland, to the town of Stans, whose tutelary mountain is the Stanserhorn (its peak is reached via an historic funicular and a one-of-a-kind open-topped gondola). The Culinarium Alpinum is a short walk from the station, in a handsome, three-storey building, surrounded by gardens, whose rows of rectangular windows with brown wooden shutters hint at its former vocation: a monastery for the Capuchin monks who occupied the premises from 1584 to 2004 (A gastronomic order: their brown-and-white hooded capes, or cappucio, inspired the word for the foam-topped cappuccino.) I was greeted by Peter Durrer, who handles operations at the Culinarium, which at first glance appears to be a restaurant, cooking school, and hotel.

The 14 guest rooms are on the upper floors; each consists of two conjoined monks' cells, and the furnishings are plain and elegant. (In keeping with the theme of monastic retreat, the rooms have no television screens; but who needs TV, when you can watch the sun setting over Alpine peaks?)

Durrer showed me around the gardens, which are explicitly presented as an edible landscape; visitors and locals are encouraged to glean herbs and berries. Monastic gardens were often the means of preserving agrobiodiversity, and sites of experimentation (think of Mendel's breakthroughs in genetics propagating peas in an Augustine monastery). The Culinarium has kept up the tradition, labelling plants with local and Latin names, and keeping a "bee hotel" to attract pollinators.

I wasn't familiar with the idea of the "Edible Community," but, while reading about the Culinarium, I learned that there are several in Britain and Europe, in both rural and urban settings. They include Todmorden in England, Andernach in Germany, the edible village of Übelbach in Austria, and the Precious Landscapes Project in Ottensheim. Residents are encouraged to plant fruit trees, herbs, berry bushes, and vegetables on window sills, in public parks, and community parks, with the idea that people can nibble as they pass by.

Which is exactly what I did as I strolled through the garden, picking ripe lingonberries and raspberries, and sampling a kind of sweet, purple-leafed basil. In keeping with the monks' cosmopolitan interests, species not native to Switzerland, but apt to grow in this climate and at this latitude, also grow in the garden, among them cherry plums, Japanese Susan, and pawpaws; all told, there are 500 varieties in the garden.

The cellar of the monastery was where the real riches were stored. Durrer showed me into a low-ceilinged cave filled with shelves lined with Mason-style jars, full of tantalizing preserves and vegetables and fruits in various stages of fermentation. Farther along was the Culinarium's shop, a one-shop stop for the gastronomic riches of the region: oils pressed from locally-grown hazelnuts and walnuts; buckwheat honey; bottles of Zama Soda, made with fresh-picked mountain herbs.

Durrer took me into a cave where huge wheels of Sbrinz cheese were stored on wooden shelves, behind glass. These are arguably the real wealth of the Culinarium: each 45-kilogram wheel is made from 600 litres of fresh raw milk, and is worth thousands of Swiss francs. Local farmers bring them to these vaults to allow them to age in a temperature-controlled environment: I sampled a two-year-old Sbrinz, which was dry, hard, and richly flavored, but the 3-year-old was the real stand-out.

Written records of a cheese called Sbrinz go back to 1530, but according to Slow Food's Ark of Taste, mountain pasture production techniques of cheese from this area go back to Roman times. To this day, there is a "Via Sbrinz," a mule track that crosses the passes of Grimsel and Gries on the way to Domodossola in Italy. I washed down the cheese with a wine glass of cloudy, pleasingly tart juice pressed from the quince trees in the garden.

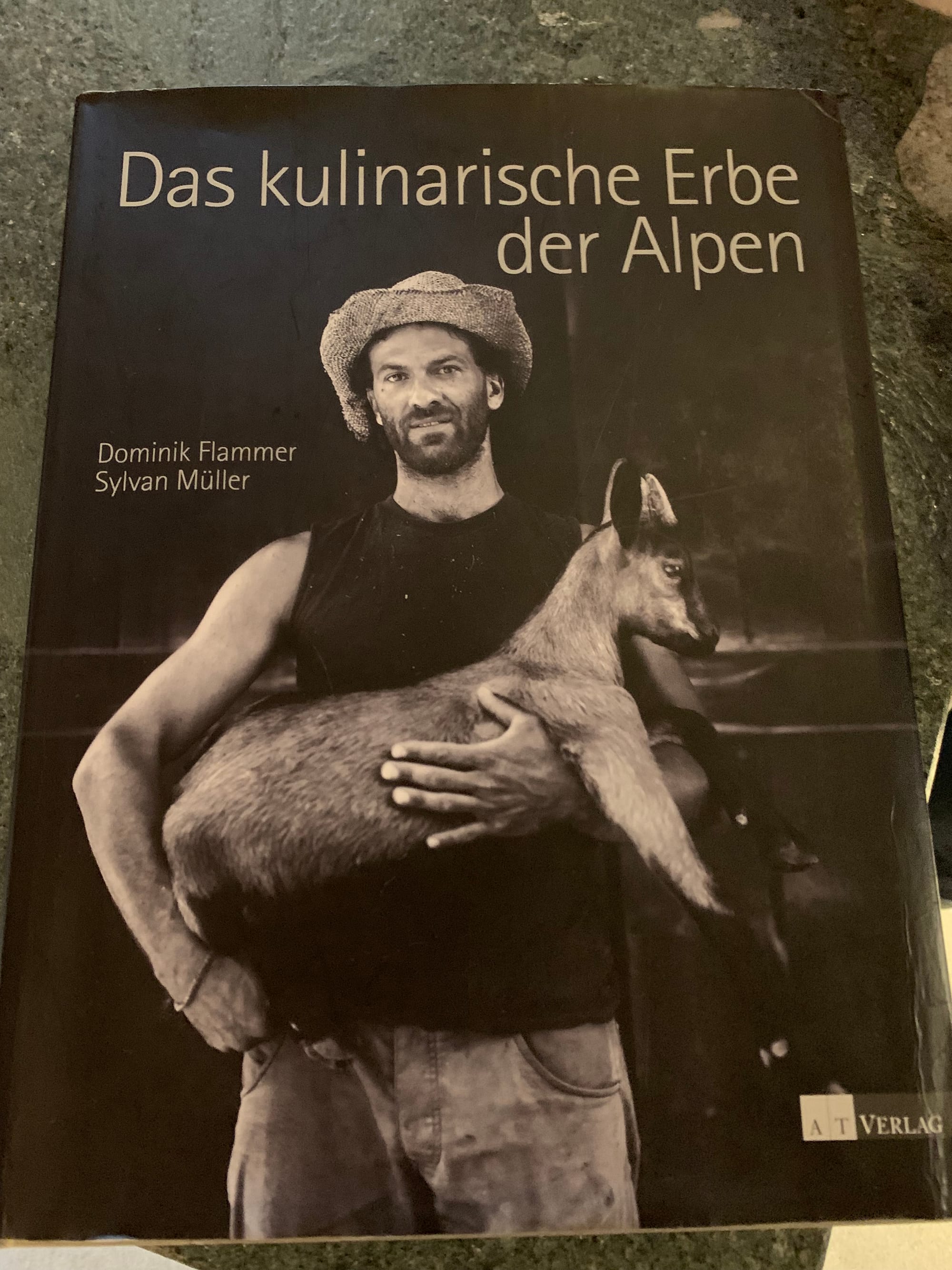

The idea for the Culinarium came from one man's infatuation with cheese: food historian and journalist Dominik Flammer, who, after writing Swiss Cheese, the authoritative book on the subject, came up with the idea for an institution celebrating mountain food. He is a passionate culinary detective, following leads to track rumors of little-known foods to their sources: a short-bodied, long-legged breed of pig known as the Black Alpine; and schnapps distilled from obscure fruits and nuts; the "wet rice" of Aargau (Flammer argues risotto was a Swiss, not an Italian, invention).

My time at the Culinarium was too short; my schedule didn't allow me to enjoy a meal on the outdoor terrace of the restaurant, whose pepper station alone was an island of diversity (Roter Kampof? Mörser? Urwaldpfeffer? I need to try them all!). But I have a feeling I will return, maybe for a few days of monastic silence and good food at the communal refectory tables. In the cloisters of the Culinarium, I sensed the animating spirit of a kindred soul; I suspect our paths will cross one day, Herr Flammer.

You'll find all the information you need on the Culinarium, in the charming town of Stans, here: https://culinarium-alpinum.com/en/