A Loaf of 3,500-year-old Sourdough

In Search of Gastronomic Treasures in Turin's Egyptian Museum

Last week I was in Italy, working on a series of food-history articles. I spent three days in Turin, an industrial city known as the “Detroit of Italy”; it’s famous for being the place where carmaker Fiat has its factories. It’s not a city many foreign tourists see, which is too bad, because it boasts butter-rich Piemontese cuisine, great vermouth, an amazing coffee museum (Turin turns out to be the birthplace of espresso), and a real treasure: the world’s first, and oldest, collection of Egyptian antiquities.

I confidently approached the museum on a Friday morning, prepared to spend several leisurely hours exploring the collections. The guard at the entrance asked me if I had a reservation; when I told her I had no such thing, she shot me a withering look. This was June 2, the Festa della Repubblica, Italy’s national holiday; not only was the museum fully booked, there were no reservations to be had the following day.

I sat down on a bench in the piazza, and, instead of weeping—no mummified crocodile tears for me—I got to work on my smartphone on the museum’s reservations site. I managed to bag a slot, the first available, for noon on Sunday—which, unfortunately, was just over two hours before my train was slated to depart for Bologna.

So when my allotted time came up, I was ready, waiting outside the entrance to the Museo Egizio. The building is an impressive multi-storey edifice of brick, originally built in 1824, which underwent a major renovation for the 2006 Winter Olympics (and another, equally successful one nine years later). This is the largest collection of Egyptian antiquities outside of Cairo. It is home to such artefacts as the Turin Erotic Papyrus, the sarcophagus of Butehamon, and the Temple of Ellesyia, an entire 18th-Dynasty cut-rock temple transported to Italy when it was threatened with being submerged by the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

But I was there to look into Egyptian food culture. I’d become obsessed with ancient breadmaking techniques during the research for my upcoming book The Lost Supper. I’d interviewed and corresponded with Seamus Blackley, the builder of the Xbox, whose side gig is recreating Egyptian breads. (You might remember Blackley made headlines a couple of years back for reviving ancient yeast, extracted from pottery kept in storage in American museums, and using it to bake beautiful loaves of bread in his backyard—over acacia wood, which is what the Egyptians would have used for fuel.) I’d gone so far as to grind my own grain on a saddle quern, a laborious process used by cultures going back not just to dynastic Egypt, but deep into the Neolithic.

The museum was crowded, in spite of the reservation system to limit visitors. It is also very large—the collections are spread over several floors. It didn’t take long, though, to find display cases full of artefacts of material culture, including striking shabtis, clay or faience statuettes (below: they were placed in tombs to stand in for the deceased, in case they should be called upon by the gods to do agricultural work in the netherworld).

I also found a wooden model of a worker kneeling over a saddle quern, using a cylindrical grinder to reduce the wheat to flour. In fact, there were models of entire bakeries, which were commonly placed in elite tombs in the Middle Kingdom. The posture was very familiar to me: you really need to get your shoulders into the work to reduce the hard grains to powder. Note the position of the feet in the model below: Egyptian remains, particularly of women, who were largely responsible for grinding grain, show their toes were bent permanently skyward—a skeletal deformation brought on by this daily grind.

My real goal was the gallery devoted to Kha and his wife Merit. This was one of the greatest finds in the history of archeology: in 1906, the Egyptologist Ernesto Schiaperelli unearthed a tomb that, unusually, hadn’t been comprehensively looted over the centuries. The tomb was also unusual in that it belonged to a non-royal: Kha was the overseer of works for Amenhotep II and III. This high-ranking architect, responsible for ensuring the immortality of the pharaohs in the afterlife, lived in a tightly-packed suburb of Thebes, known as Deir El-Medina. When the fully intact tomb was opened, it was just as it was when it was sealed 3,400 years earlier. It contained the couple’s sarcophagi, which in turn contained their mummies—which have yet to be unwrapped. It contained a copy of the Book of the Dead, an inscribed golden cubit (an architect’s measuring stick), coffers packed with linen, Merit’s alabaster perfume bottles, and even Kha’s hip flask.

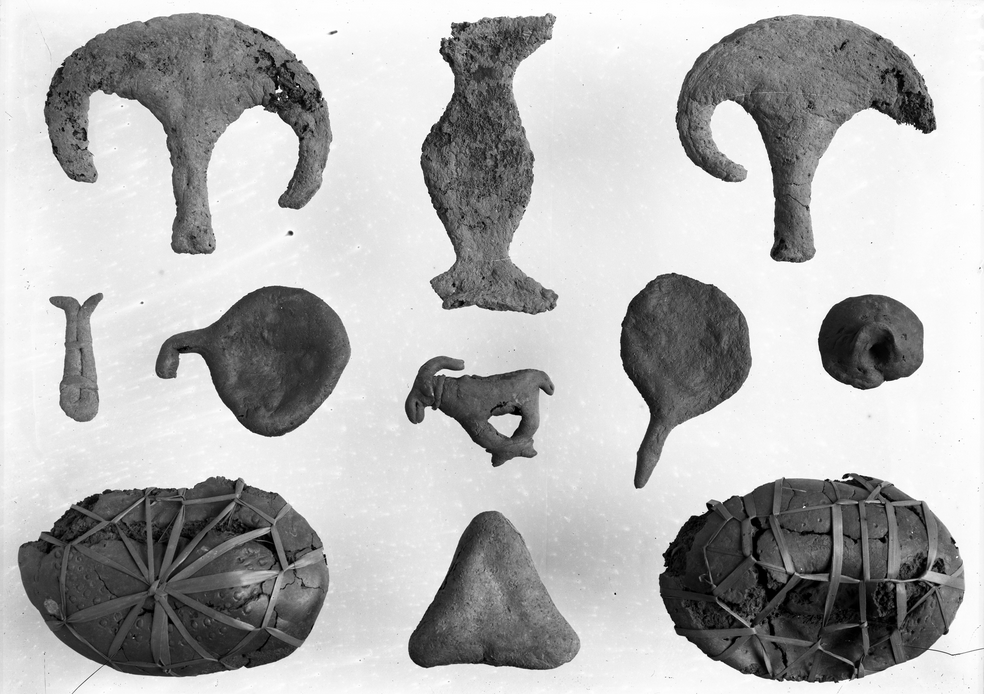

It also contained food. There were 13 alabaster jars for vegetable oils, many of which remain hermetically sealed. (Some may also have been sacred oils used in the embalming process.) There were amphorae full of poultry, flour, beer, and wine; some of the wine jars even bear inscriptions indicating the name of the vineyard and the storage date. There were bowls laid out with dried fruits, birds, and fish. And there was dessert: a nasty-looking, blackened pyramid that the museum identifies as a “carob compote” (see below). A feast for the afterlife—go ahead, you can have the first bite.

The breads on display had resisted the sands of time much better. Fifty loaves were found in the tomb; some were baked in the shape of animals, like striding gazelles or antelopes, but most were full-on loaves: boules that would pass muster in any contemporary artisanal bakery. In fact, there was a nice touch that today’s bakers could learn from: many were gift-wrapped in strands of papyrus, adding a certain je-ne-sais-quoi to the whole package.

Most of these loaves were baked from emmer, the wheat that I used to make my Neolithic flatbread. Ancient Egypt ran on bread and beer; Kha was paid in grain, which he could then barter for other goods and services. The village where Kha and Merit lived featured a state-supplied granary. Kha would have received five and a half sacks of emmer wheat, and two sacks of barley, as his monthly salary. And the bread that he and Merit ate would have been tasty: the dough was mixed with cumin, coriander, dates, honey, and other delightful flavorings.

In rural Egypt, bread is still baked in mudbrick ovens of the kind found in excavations of the village of Deir El-Medina. Kha would have walked to work to oversee the construction of pharaonic tombs in the Valley of the Kings, a few kilometers away, perhaps packing his daily bread with him. Thanks to the fluke of its preservation, we know exactly what that bread looked like—I was looking at the nearly four millennia-old loaves in the display case. But can we know what it, or other ancient Egyptian foods, tasted like?

I believe we can. Because Egyptologists resisted the urge to unseal some of the jars in the tombs, the organic remains within are intact. Analytical chemists have placed the vessels from Kha’s tomb in plastic bags to collect the volatile compounds without harming the contents; they’ve pinpointed the aldehydes, long-chain hydrocarbons and ohter substances associated with beeswax, fruits and dried fish. There’s even talk of trying to recreate the “smellscape” of an Egyptian tomb for contemporary museum visitors.

In the meantime, in the absence of a complete molecular recreation of ancient foods, we can come tantalizingly close to tasting the bread the ancient Egyptians enjoyed. We know what kind of grain they used, how they ground it, what kind of ovens they used, and, thanks to Mr. Blackley, the strains of yeast that made the dough rise.

My whirlwind visit ended all too quickly (and yes, I did make it to the train station on time). But even a short exposure to such wonders has had its effect. Thanks to the Museo Egizio, I’m continuing to travel in my imagination—and back in time.

_____

…I hope you’re enjoying these dispatches! This one is free, but not all of them will be. Consider becoming a founding member or upgrading to a paid subscription to continue following all my culinary adventures.